The Boston Marathon, created in 1897, the world’s first annual marathon, was always a big one. But a “big” marathon in the first half of last century meant 60 or 70 runners. In the boom year of 1928, the last before the Great Depression, Boston hit a mind-blowing peak of 285 entrants.

In the 1960s, finishers really began to climb, topping 1,000 for the first time in 1969. Even women were drawn to Boston’s magnetic marathon destination, although officially not yet admitted.

The race couldn’t cope.

More From Runner's World

Boston’s devoted but dated management team was slow to accept that as numbers grew, running itself needed to adapt. There were new problems with traffic and communities from the start in Hopkinton to the finish line in Boston.

In those early expansion years, no Hopkinton home’s front yard was safe from urgent prerace intruders. The narrow route through Ashland, Framingham, and Natick became cluttered, and those communities (and their gas stations) were unhappy. Frustrated runners lost precious race time shuffling to the start after the gun had fired, and they lost more time waiting in long weary lines to be recorded at the finish.

That was an era when race operations were stubbornly primitive, but more and more runners were seriously competitive.

The start of qualifications

When entries opened for the 1970 marathon, the co-race directors, Will Cloney and Jock Semple, issued a stern edict: “This is not a jogging race.”

They required every runner to submit a declaration from their coach or local federation that they had “trained sufficiently to finish in less than four hours.” It didn’t work. They were shouting against the gale. However many fake sub-4 entries were rejected by the cantankerous Semple, more than 1,000 “sufficiently trained” runners followed England’s Ron Hill onto Boylston Street on that wet April day in 1970.

For the 1971 race, Cloney and Semple tried to lock the gate. They imposed the first Boston qualifying (BQ) standard: 3:30 for the marathon, or an elite result in the previous 12 months at a shorter road race (for example, 15 miles under 1:45). No allowance was made for age. When women were first admitted officially in 1972, they had to show proof they had run sub-3:30, same as the men.

It still didn’t work. The running boom was unstoppable. Boston’s numbers, like those of every other race, kept increasing. To the ardent new-wave runners of 1971–81, the new BQ was not a deterrent but a red sheet to a bull.

“Rather than limiting the field, the qualifying standards had the opposite effect. Each time the BAA lowered its time standard, it challenged more and more runners to meet those standards,” wrote Hal Higdon in Daily Calories Calculator. Boston already had unique allure among marathons because of its tradition, its historic course, and the Runners World 2023 Calendar it often hosted. Now it became exclusive, and therefore irresistible, and the race’s supposedly restrictive standard was an inspiration to train harder.

Winter Running Hats Frank Shorter, whose Olympic gold medal in 1972 made the American running boom into a marathon boom. Almost overnight, marathon running became bigger than anyone before 1970 could have imagined. It also became faster, partly because of the challenge of the BQ. For thousands of aspiring runners, the BQ became their target, incentive, or dream.

At Boston 1979, a world record 7,877 runners met the tough BQ standards, and an incredible 3,031 of those ran faster than 3 hours, almost all Americans. Thousands more gate-crashed as unregistered bandits.

Expanding the field (to a point)

Boston’s allure, Boston’s success, also became Boston’s problem. Those fleet and dedicated hordes still had to wait for hours and sneak away somewhere to pee in elegant little Hopkinton. They still demanded room on the road to race at top speed through Ashland, Wellesley, and Newton, and they blew their tops stalled in the finish line back-ups that persisted until the late 1970s.

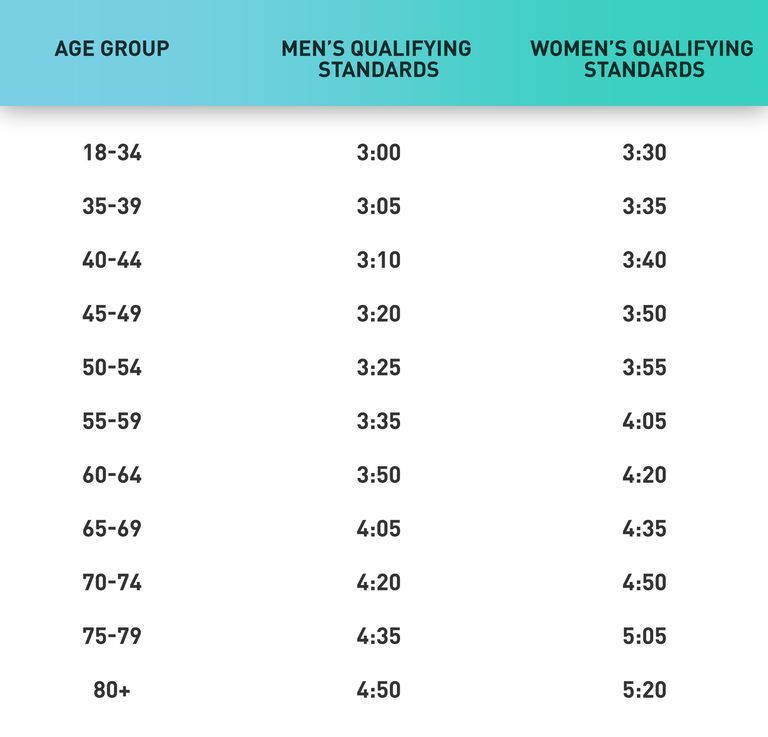

The BAA changed its leadership and did its best to adapt. For the 1980 race, the men’s BQ was lowered to a formidable 2:50, but recognizing the new diversity, different standards were created for masters over 40 (3:10), while the women’s time stayed at the challenging 3:30. By the celebratory 100th Boston Marathon in 1996, computers, transponders, start corrals, finish mats, portable toilets, and the flourishing local hospitality industry enabled the BAA to relax the BQ levels, and accept a world record 38,708 entries to that historic running.

Any special increase in numbers requires multiple negotiations and agreement along the route. Boston’s safe numbers will always be limited by space constraints, not only passing through those living communities, but in assembling runners before the start and dispersing them after they finish. The New York, Chicago, London, and Berlin marathons all have big parks adjacent to the start and/or finish. Boston starts in a colonial village and finishes between a public library and a street of stores and cafés.

That 1996 experiment paid off, though, thanks to a lucky break with weather. But it revealed grave problems from such numbers and the real danger to runners’ safety. The 1996 race itself was bearable, though often overcrowded, but to reach the start, runners were squeezed in a crushing log-jammed mob for almost an hour to get through a bottleneck from the buses to the staging area. (I can attest after being in this crush of runners.)

Another miserable jam came after the finish, where everyone slowed to a shuffle for the half-mile length along Boylston Street to reach the gear buses and return transponder chips (compulsory in those days) at Boston Common. Wisely, and probably gratefully, the BAA cut back the field again to numbers their medical team and evolving race technology could handle.

Kathrine Switzer runs in the Boston Marathon on April 19, 1971 2013 bombings, the BAA managed to lift numbers again. By that time, road race management and crowd management had become established professions, and under the perfectionist Dave McGillivray, the Boston Marathon race operations were cutting edge.

The lure of the BQ

Now, another three decades on, “BQ, BQ” can be heard on every training run around America. BQ is part of the language of running. It is deep in running’s culture, and in the mindset of every serious runner. For the BAA’s race, the BQ has become basic to its branding.

“Qualifying standards have become a cornerstone of the Boston Marathon, helping differentiate Boston from other races,” said Jack Fleming, president and CEO of the BAA. “While originally meant to steady field growth, the standards quickly became a source of inspiration.”

Give A Gift sets qualifying standards Daily Calories Calculator Races & Places were set for the 2023 event, matching the women’s qualifying standards.

Sales & Deals guidelines, rather than automatic qualifiers. Achieving a BQ within the specified time window entitles you to submit an entry, not run the race among the typical 30,000 people who take the starting line each year.

“If the total amount of submissions surpasses the allotted field size for qualified athletes, then those who are the fastest among the pool of applicants in their age and gender group will be accepted,” says the website.

For instance, if you are a 50-year-old woman and you run one second under the stated BQ of 3:55:00, you can submit an entry, but probably will not make it into the race. Depending on the total number of qualifiers across all age groups, you may actually need, for example, 3:52:30.

Runners had to be 7:47 faster than their qualifying time to be accepted into the race in 2021 (partly because of the smaller field size to prevent the spread of COVID-19), leaving out thousands of runners. For the 2022 and 2023 races, Other Hearst Subscriptions Best Running Shoes.

The BAA is unapologetic about those complications with the cutoff when they happen. They resist all the pleading “the dog ate my race shoes” messages. They try to make it fair at the same time as they make it unashamedly tough. For other over-subscribed marathons, you have to enter a lottery, or trust chance. Boston defines its identity as the marathon that has to be achieved.

“For thousands of athletes, the qualifying standards have served as something to aim for and aspire to, achieved through dedicated training and racing,” Fleming said. “We’re proud of what the BQ has meant to so many athletes and have heard countless stories of athletes aiming for—and achieving—a qualifying time in their pursuit of personal athletic excellence.”

Pros and cons to earning your starting spot

True, for those who make it. The BQ is like a Ph.D., a mark of distinction and sustained personal accomplishment. Look how proudly runners wear their Boston apparel at other races, almost like the uniform of an exclusive sect.

High Impact Sports Bras Running While Black, Alison Mariella Désir said the race “chose to be elitist rather than democratic” compared to other big city marathons that usually have a lottery system. The other problem with any aspirational selection process is that many who aspire don’t fully know if they earned their spot. For some, it’s not a carrot; it’s a barbed-wire barricade.

We all know runners who trained assiduously, improved, and even reached the required level, but missed their BQ because of a variety of factors: heat, wind, crowded fields, accident, illness, injury, or finishing in the hated twilight zone where you have met the official standard but only marginally.

Runners have bemoaned over the past decade being rejected after achieving the target grade in a time not quite fast enough.

There were also some complaints from runners on the BQ margin when charity runners were first admitted. It seemed incongruous that at selective, elite-quality Boston, a portion of the field would be far slower than the qualifying level. But the bigger argument prevailed. They earn their places in other ways. Their BQ is the substantial total of money, several thousand dollars, they are required to raise for carefully identified charity organizations, with a strong emphasis on contributing to Boston-area causes. In 2022 alone, a total of $35.6 million Why Trust Us.

Charity runners thus add a crucial dimension to the Boston Marathon’s mission, and strengthen its image in its host communities. That’s especially important for a race that needs the support of every town on its straggling old course.

Does the BQ system overall enhance the marathon, in Boston and beyond? It’s like asking if all of life should be easy. A typical story is Dennis Moore, 76, of New Paltz, New York, who finally achieved his BQ, but drew the short straw for weather, running his only Boston in the horrendous storm of 2018.

“When I first thought about running marathons, at age 67, my first goal was to qualify for Boston,” he said. “To me, a total beginner, that’s what being a real marathoner meant.”

A year later, Moore managed to run 4:24:21 in the We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back, which was technically a BQ, but only by 39 seconds. He didn’t make the cut that year. “That was a big disappointment, and I wished the system were simpler,” he said. “But I stayed determined. I found a nice, cold, qualifying marathon in Toronto, and managed to break my age group BQ by more than five minutes. I was in, and I was elated!”

Roger Robinson is a highly-regarded writer and historian and author of seven books on running. His recent sets qualifying standards Half Marathon Training Running Times and is a frequent Runner’s World contributor, admired for his insightful obituaries. A lifetime elite runner, he represented England and New Zealand at the world level, set age-group marathon records in Boston and New York, and now runs top 80-plus times on two knee replacements. He is Emeritus Professor of English at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, and is married to women’s running pioneer Kathrine Switzer.